Professor, Faculty of Business and Commerce, Keio University

Toshiaki Ushijima

Industrial History, Business History

Assumed current position in 2017, after serving as research assistant, full-time lecturer, and assistant professor at the Faculty of Business and Commerce, Keio University.

Author of “Asymmetry of Information, Trust-Building and Market Quality: Governing the Quality of Goods in Modern Asia” (with K. Furuta, Imitation, Counterfeiting and the Quality of Goods in Modern Asian History, Springer, 2017), “Hokkaido Colliery & Steamship Co., Ltd. President Kichitaro Hagiwara — Fighting Against the Decline of the Coal Industry” (in Managers Who Transcended Their Times, edited/authored by Shigehiko Ioku, Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha, 2017, in Japanese), etc.

Managing Decline

Faculty of Business and Commerce, Keio University Toshiaki Ushijima

I think many people, when considering Japanese industry, are probably interested in topics like which industries have led economic growth in the past and what industries will grow in the future. However, my main interest lies in how people, companies, local governments, and the national government involved with industries forced into decline have faced such decline.

How is decline managed?

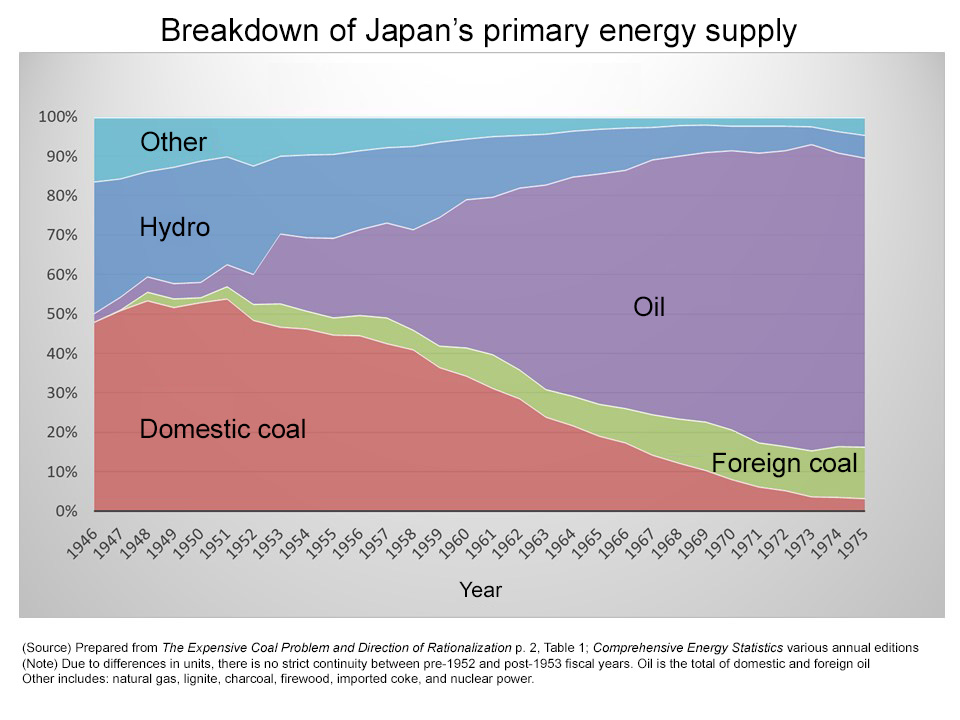

For example, it is no exaggeration to say that the coal industry once stood at the center of industry and the economy as the most important primary energy supply industry supporting Japan’s energy needs. However, the coal industry rapidly lost its competitiveness due to the energy revolution that began in the 1950s. Coal came to be positioned as a high-cost, inefficient energy source due to the rise of oil as a new energy source.

This change was not just a problem for business management; it had serious impacts on entire local communities. In regions that were particularly dependent on the coal industry, various problems emerged, such as increased unemployment due to mine closures, stagnation of the local economy, and population outflow.

In response to this serious situation, the government aimed to reduce the social impact of the rapid decline of the coal industry and pursue a more gradual “phased withdrawal.” Financial assistance, re-employment support, regional development measures, and other steps for companies, communities, coal industry workers, and local governments were introduced, and these policies continued for about 40 years. What the case of the coal industry demonstrates is that the larger the industry, and the more important it is to the local economy, the more extreme the shock caused by its decline. Therefore, the question of how to minimize the damage to people’s livelihoods and the local economy caused by the sudden collapse of an industry, i.e., “how to manage decline,” becomes a major issue.

The burden of support and social consensus

Support policies to avoid sudden changes and achieve a soft landing are extremely important, but at the same time face difficult challenges. In post-war Japan, various withdrawal support measures were implemented as industrial adjustment policies for structurally depressed industries other than the coal industry. However, these policies end up allocating precious policy resources to industries and regions that, so to speak, have no future. The question becomes to what extent social consensus can be obtained regarding the fiscal burdens.

In recent years, during discussions about reconstruction of areas struck by major earthquakes, a certain member of the Diet argued that “in depopulated villages where maintenance was difficult even before the earthquake, relocation should be properly and systematically chosen over reconstruction,” which led to a major controversy with a mix of opinions both pro and con. Although the situations are different, problems related to the decline of industries and regions are likely structurally the same. The longer the support continues, and the greater the necessary costs become, the more questionable it becomes whether consensus can be obtained from society as a whole, including people other than those directly involved, to continue the support. Some people will absolutely believe support is necessary, while others will say such things are not needed. This involves extremely difficult judgments about how to reconcile differences of opinion and translate them into policy.

Dependence on support and sense of crisis

On the other hand, those who receive assistance also face various challenges. A certain period of time must be provided to achieve a soft landing. During that time, minimal support is continued to allow companies and regions to survive. The aim is to buy time and search for the next path, but if it’s assumed that support will definitely continue for a certain period, there’s also an aspect where this gradually becomes taken for granted. One could express this as support dependency becoming normalized. Support to prevent disastrous damage is always necessary as part of declining industry policies, but when aid to overcome immediate difficulties continues, it may ultimately slow down the speed of making decisions to withdraw or moving toward new paths. Even if support is initially planned to end in 10 years, when we actually look at the situation after 10 years, the judgment becomes “if we cut off aid here, it will collapse” and “since this policy was started to prevent collapse, we need to continue.” We can start it, but we can’t find an exit strategy. Determining the time to end support in a way that aligns with the original purpose is also extremely difficult.

Of course, declining industries and regions also have a strong sense of crisis. For example, in the former coal mining area of Hokkaido’s Yubari City, which experienced financial collapse due to failed large investments in tourism facilities, they actively aimed to create new regional industries by leveraging an environment where funds could be raised under favorable conditions through support policies. In the backdrop of such investments, there was likely a strong sense of crisis about the future of the region. However, it’s likely that precisely due to the strong sense of crisis, excessive investments—dependent on government policies aimed at softening the shock of decline—were made, leading ultimately to fiscal collapse.

While dependence and a sense of crisis give a strong impression of being in opposition, in declining industries and regions, these two coexist. Which one appears more strongly differs depending on the timing and situation, but the combination of dependence and a sense of crisis can also give rise to new problems.

Looking toward the future

The decline of the coal industry may be an extreme example. However, in today’s Japan, there are many regions facing the decline of local industries, depopulation, and aging. How should the people, businesses, and governments living in these regions respond to decline? Also, how should support for declining regions and industries be structured, how long should it continue, and who should make these decisions and how? This will become a major issue that we will inevitably have to discuss repeatedly in the future.

In the seminar I supervise, we are engaged in continuing activities in rural mountainous areas called “marginal villages” and projects relating to food and agriculture. Along with analyzing historical cases, we must understand the current situation of industries and regions facing decline. We must also ask: What can and cannot be done to protect people’s livelihoods and maintain local communities? Together with my students, I want to continue thinking about the major challenges we will face in the future.

References

Shinya Sugiyama and Toshiaki Ushijima (editors/authors), The Decline of the Japanese Coal Industry: Companies and Regions in Post-War Hokkaido (Keio University Press, 2012) (in Japanese).

Toshiaki Ushijima, “Hokkaido Colliery & Steamship Co., Ltd. President Kichitaro Hagiwara — Fighting Against the Decline of the Coal Industry” (in Managers Who Transcended Their Times, edited/authored by Shigehiko Ioku, Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha, 2017, in Japanese).